Nine years ago, I joined over eight hundred others in Encinitas, California and listened to three veterans tell stories about their time at war. They read their contributions to the anthology, Operation Homecoming, a collection of emails, journals, correspondence, essays and fiction written by those who were were deployed and their families.

Almost everyone there seemed to have a relationship with the military, past or present. I did not. Self consciousness surged through me as I took my seat before the readings. Would I be viewed with an insider’s disdain for outsiders or outed and dismissed as the liberal I was with all the baggage that comes with it? Would I have been there if I hadn’t been writing a novel about a family impacted by the war?

No one cared. People nodded hello. They smiled. Then we all focused, together, on the stage in front of us while a Camp Pendleton Marine, a Navy Petty Officer 1st class, and a retired Air Force lieutenant shared a bit of what they’d witnessed or experienced when they went to war.

As I listened, I realized that, regardless of what brought me to the auditorium, I needed to be there. Something had driven the veterans on the stage to write their stories and to share them out loud where we could hear them. The physical presence of all of us in that room created its own energy and, for a while, united us.

That connection is elusive. The numbers tell part of the story: only 1% of the American population serves in the military. For many in the 99%, our connection with the military ended with our father’s generation and was sealed by the suspension of the draft. Geography also plays a role: our wars are fought thousands of miles from our backyards; they don’t disrupt our jobs, our families, our plans. It is possible for most of us to live our lives untouched by war — and by the men and women who have fought them.

We in the 99% can say thank you. We can give money to organizations that help veterans with everything from health to education to jobs. We pay taxes that help pay for the war and medical care afterward. We can do all of these things without understanding a single thing about what veterans experienced and what they and their families face when they come home. Because there is no draft anymore, we can also say that they chose to enlist in military on their own. Lurking beneath that, though, are uncomfortable questions that bring responsibility back to our doorsteps: What if they hadn’t volunteered? What if no one signed up?

The stories I heard that night in the Encinitas auditorium did not change how I felt about war in general but they, along with every veteran’s story I’ve read or heard before or since, has changed me in ways I’m still discovering. The same is true when I read fiction that translate for me the conflicts – internal and external – faced by those who go to war enlist in the military and are deployed.

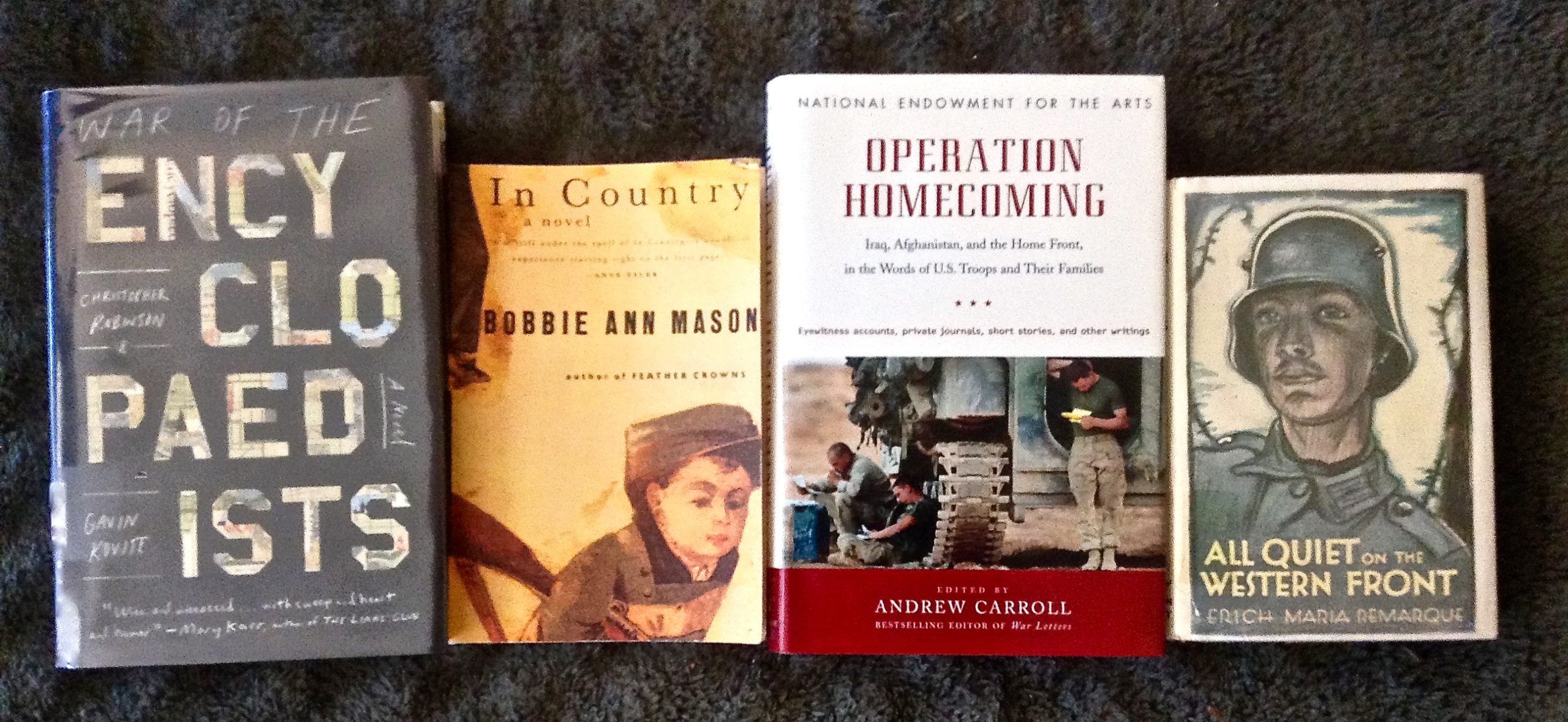

I can never truly know what it is like to be inside the experience of a soldier who has served three combat deployments, or how his wife feels each time he leaves. But I can empathize more completely now because of projects like Operation Homecoming or a collection of short stories like Phil Klay’s Redeployment or Siobhan Fallon’s You Know When The Men Are Gone.

I can see which of the problems they face are related to war and which are the stuff of being human in our world. I can imagine more completely how alienating it might feel to reenter our society with its emphasis on the individual. I can, without self consciousness, sit across the table from a Marine who returned from Iraq, eat lunch, engage in conversation that covers everything from deep personal loss in the wake of the Iraq war, to family history, to the joy his young daughter brings him.

There is much he and I don’t know about each other and much we may never know or understand, but we are no longer strangers. It’s a beginning.

Connecting Through Stories: Places to Start

Many resources are available to veterans who want to write or tell their stories and for the rest of us who want to read or hear them. In addition, a new generation of writers are adding to the canon of war literature that stretches back thousands of years. I’ve put together a beginning list of links that serve as a starting point for all of us to use to help keep us connected with each other.

You’ll find links for organizations, resources, and books that can help get you started. You’ll find a heavy but not exclusive emphasis on our most recent wars but this is likely to change. The list is evolving and all suggestions are welcome.

VETERANS WRITE: Organizations that help veterans write their stories, some with a focus on healing and others with an additional mission to reach common ground through literature

SPOKEN WORD: Documentaries, video series and radio programming that bring these stories alive through the spoken word

ONLINE: Blogs, sites, podcasts, interviews, book reviews and more for readers and writers by veterans, military families, and civilians

FICTION, NONFICTION, POETRY: Novels, memoir, poetry, anthologies, and lists of books recommended by reviewers, writers, and readers in the literary community. You’ll find work by veterans, civilians, military families that explores the impact of war

FEATURED LINKS: Each month, I’ll highlight organizations, books, resources, articles

Beautiful and motivating Betsy. Thank you.

Nobody asked me, but I’m of the belief we as a society need many, many more of our citizens otherwise unconnected with the ugly business of war to take a deep drink of it. Among the things that should shame us, (IMO) was the cheerleader, spectator sport we turned both Gulf Wars into.

The sanitized view of it from afar is nothing like it’s tastes, smells & it’s gut gnawing impact. Thanks so much for your post & for Casualties, the reading of which I enjoyed (& shed a tear or three over). Which is my back-handed way of saying “great work!”

Dirk, a long overdue reply for your thoughtful comment. Thank you for checking in here and for expressing so well why we all have a responsibility to shrink the civilian-military gap.